Seven-time Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong has denied numerous accusations of doping over the years. Look back at his record-setting career.

Seven-time Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong has denied numerous accusations of doping over the years. Look back at his record-setting career.  Armstrong, 17, competes in the Jeep Triathlon Grand Prix in 1988. He became a professional triathlete at age 16 and joined the U.S. National Cycling Team two years later.

Armstrong, 17, competes in the Jeep Triathlon Grand Prix in 1988. He became a professional triathlete at age 16 and joined the U.S. National Cycling Team two years later.  In 1995, Armstrong wins the 18th stage of the Tour de France. He finished 36th overall and finished the race for the first time that year.

In 1995, Armstrong wins the 18th stage of the Tour de France. He finished 36th overall and finished the race for the first time that year.  Armstrong rides for charity in May 1998 at the Ikon Ride for the Roses to benefit the Lance Armstrong Foundation. He established the foundation to benefit cancer research after being diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1996. After treatment, he was declared cancer-free in February 1997.

Armstrong rides for charity in May 1998 at the Ikon Ride for the Roses to benefit the Lance Armstrong Foundation. He established the foundation to benefit cancer research after being diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1996. After treatment, he was declared cancer-free in February 1997.  Armstrong takes his honor lap on the Champs-Élysées in Paris after winning the Tour de France for the first time in 1999.

Armstrong takes his honor lap on the Champs-Élysées in Paris after winning the Tour de France for the first time in 1999.  After winning the 2000 Tour de France, Armstrong holds his son Luke on his shoulders.

After winning the 2000 Tour de France, Armstrong holds his son Luke on his shoulders.  Armstrong rides during the 18th stage of the 2001 Tour de France. He won the tour that year for the third consecutive time.

Armstrong rides during the 18th stage of the 2001 Tour de France. He won the tour that year for the third consecutive time.  Armstrong celebrates winning the 10th stage of the Tour de France in 2001.

Armstrong celebrates winning the 10th stage of the Tour de France in 2001.  After winning the 2001 Tour de France, Armstrong presents President George W. Bush with a U.S. Postal Service yellow jersey and a replica of the bike he used to win the race.

After winning the 2001 Tour de France, Armstrong presents President George W. Bush with a U.S. Postal Service yellow jersey and a replica of the bike he used to win the race.  Armstrong celebrates on the podium after winning the Tour de France by 61 seconds in 2003. It was his fifth consecutive win.

Armstrong celebrates on the podium after winning the Tour de France by 61 seconds in 2003. It was his fifth consecutive win.  Jay Leno interviews Armstrong on "The Tonight Show" in 2003.

Jay Leno interviews Armstrong on "The Tonight Show" in 2003.  After his six consecutive Tour de France win in 2004, Armstrong attends a celebration in his honor in front of the Texas State Capitol in Austin.

After his six consecutive Tour de France win in 2004, Armstrong attends a celebration in his honor in front of the Texas State Capitol in Austin.  Armstrong arrives at the 2005 American Music Awards in Los Angeles with his then-fiancee Sheryl Crow. The couple never made it down the aisle, splitting up the following year.

Armstrong arrives at the 2005 American Music Awards in Los Angeles with his then-fiancee Sheryl Crow. The couple never made it down the aisle, splitting up the following year.  Armstrong holds up a paper displaying the number seven at the start of the Tour de France in 2005. He went on to win his seventh consecutive victory.

Armstrong holds up a paper displaying the number seven at the start of the Tour de France in 2005. He went on to win his seventh consecutive victory.  As a cancer survivor, Armstrong testifies during a Senate hearing in 2008 on Capitol Hill. The hearing focused on finding a cure for cancer in the 21st century.

As a cancer survivor, Armstrong testifies during a Senate hearing in 2008 on Capitol Hill. The hearing focused on finding a cure for cancer in the 21st century.  In 2009, Armstrong suffers a broken collarbone after falling during a race in Spain along with more than a dozen other riders.

In 2009, Armstrong suffers a broken collarbone after falling during a race in Spain along with more than a dozen other riders.  Young Armstrong fans write messages on the ground using yellow chalk ahead of the 2009 Tour de France. He came in third place that year.

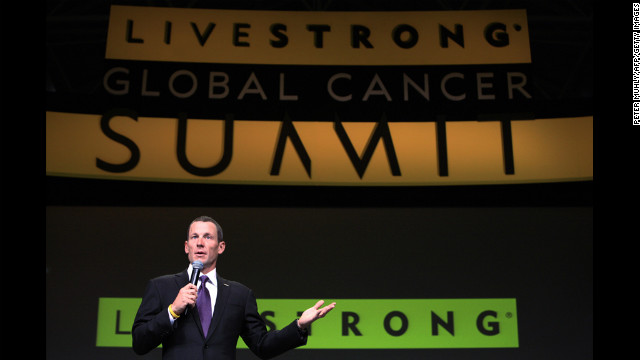

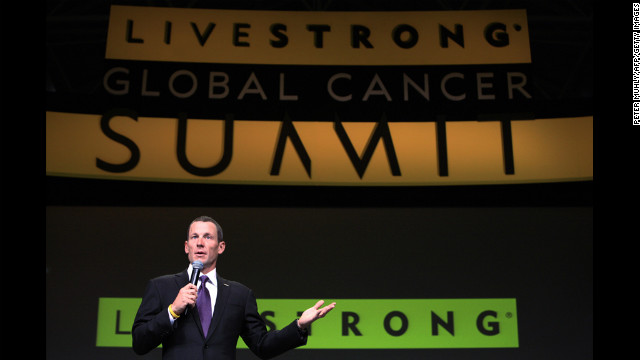

Young Armstrong fans write messages on the ground using yellow chalk ahead of the 2009 Tour de France. He came in third place that year.  Armstrong launches the three-day Livestrong Global Cancer Summit in 2009 in Dublin, Ireland. The event was organized by his foundation.

Armstrong launches the three-day Livestrong Global Cancer Summit in 2009 in Dublin, Ireland. The event was organized by his foundation.  In May 2010, Armstrong crashes during the Amgen Tour of California and is taken to the hospital. That same day, he denied allegations of doping made by former teammate Floyd Landis.

In May 2010, Armstrong crashes during the Amgen Tour of California and is taken to the hospital. That same day, he denied allegations of doping made by former teammate Floyd Landis.  Ahead of what he said would be his last Tour de France, Armstrong gears up for the start of the race in 2010.

Ahead of what he said would be his last Tour de France, Armstrong gears up for the start of the race in 2010.  Lance Armstrong looks back as he rides in a breakaway during the 2010 Tour de France.

Lance Armstrong looks back as he rides in a breakaway during the 2010 Tour de France.  Armstrong finishes 23rd in the 2010 Tour de France. He announced his retirement from the world of professional cycling in February 2011. He said he wants to devote more time to his family and the fight against cancer.

Armstrong finishes 23rd in the 2010 Tour de France. He announced his retirement from the world of professional cycling in February 2011. He said he wants to devote more time to his family and the fight against cancer.  Armstrong's son Luke; twin daughters, Isabelle and Grace; and 1-year-old son, Max, stand outside the Radioshack team bus on a rest day during the 2010 Tour de France.

Armstrong's son Luke; twin daughters, Isabelle and Grace; and 1-year-old son, Max, stand outside the Radioshack team bus on a rest day during the 2010 Tour de France.  The frame of Armstrong's bike is engraved with the names of his four children at the time and the Spanish word for five, "cinco." His fifth child, Olivia, was born in October 2010.

The frame of Armstrong's bike is engraved with the names of his four children at the time and the Spanish word for five, "cinco." His fifth child, Olivia, was born in October 2010.  In February 2012, Armstrong competes in the 70.3 Ironman Triathlon in Panama City. He went on to claim two Half Ironman triathlon titles by June. He got back into the sport after retiring from professional cycling.

In February 2012, Armstrong competes in the 70.3 Ironman Triathlon in Panama City. He went on to claim two Half Ironman triathlon titles by June. He got back into the sport after retiring from professional cycling. - "We hid" from drug tests, cyclist Tyler Hamilton told doping investigators

- Tipoffs and timing helped conceal drug use as well, report finds

- Armstrong denies doping allegations

(CNN) -- Blood transfusions. Saline injections. Back-dated prescriptions and tipoffs to coming tests.

Former teammates of cycling superstar Lance Armstrong recounted a wide range of techniques used to beat the sport's drug-testing regimen to investigators from the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, which released its findings on the seven-time Tour de France winner Wednesday. But perhaps the most effective one was the most low-tech: laying low.

Attorney: Armstrong case a 'witch hunt'

Attorney: Armstrong case a 'witch hunt'  'Dope, or don't compete at highest level'

'Dope, or don't compete at highest level'  Brennan on Armstrong: 'He gave up'

Brennan on Armstrong: 'He gave up'  Armstrong won't fight doping charges

Armstrong won't fight doping charges "We hid," the report quotes former U.S. Postal Service team member Tyler Hamilton. "At the time, the whereabouts programs of drug testing agencies were not very robust." The sport's international governing body, the UCI, "did not even have an out of competition testing program. If a tester did show up, you typically would not get a missed test even if you decided not to answer the door. In any case, there was no penalty until you had missed three tests. So, avoiding testing was just one more way we gamed the system."

Highlights of the Armstrong report

The team's staff "was good at being able to predict when riders would be tested and seemed to have inside information about the testing," states the nearly 200-page decision, which was backed by hundreds of pages of supporting documents.

During Armstrong's comeback attempt in 2009, his Astana team "benefited from privileged information or timing advantages during doping control tests." And in 2010, Armstrong himself "was providing untimely and incomplete whereabouts information to USADA, thereby making it more difficult to locate him for out of competition testing."

Armstrong has consistently denied doping accusations, and his lawyer called the USADA probe a "witch hunt" Wednesday. But he has stopped contesting the allegations, and he faces being stripped of his titles.

The riders also told of timing their use of rythropoietin, or EPO, which boosts the number of red blood cells that carry oxygen to the muscles, to avoid detection. The substance was undetectable before 2000 and currently can be detected only for a short time. The riders cut that time further by injecting it into a vein rather than under the skin, meaning it would be gone "in a matter of hours."

Evidence of Armstrong doping 'overwhelming,' agency says

They used testosterone in much the same way, taking small doses at night so that they could pass a drug test the following morning. And they also had infusions of saline solution before a test, which throws off a test that measures red blood cell concentration.

That sometimes required fancy footwork, and there were some close calls, the riders said.

During the 1998 world cycling championships, a UCI tester showed up unannounced and started setting up at a bed and breakfast where Armstrong's team was staying. A team doctor went outside to their car, retrieved a bottle of saline "and smuggled it right past the UCI tester and into Armstrong's bedroom," the report states.

Teammate Jonathan Vaughters told investigators that they later "had a good laugh about how he had been able to smuggle in saline and administer it to Lance essentially under the UCI inspector's nose."

Armstrong: It's time to move forward

CNN's Matt Smith and Steve Almasy contributed to this report.

Attorney: Armstrong case a 'witch hunt'

Attorney: Armstrong case a 'witch hunt'  'Dope, or don't compete at highest level'

'Dope, or don't compete at highest level'  Brennan on Armstrong: 'He gave up'

Brennan on Armstrong: 'He gave up'  Armstrong won't fight doping charges

Armstrong won't fight doping charges

Seven-time Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong has denied numerous accusations of doping over the years. Look back at his record-setting career.

Seven-time Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong has denied numerous accusations of doping over the years. Look back at his record-setting career.  Armstrong, 17, competes in the Jeep Triathlon Grand Prix in 1988. He became a professional triathlete at age 16 and joined the U.S. National Cycling Team two years later.

Armstrong, 17, competes in the Jeep Triathlon Grand Prix in 1988. He became a professional triathlete at age 16 and joined the U.S. National Cycling Team two years later.  In 1995, Armstrong wins the 18th stage of the Tour de France. He finished 36th overall and finished the race for the first time that year.

In 1995, Armstrong wins the 18th stage of the Tour de France. He finished 36th overall and finished the race for the first time that year.  Armstrong rides for charity in May 1998 at the Ikon Ride for the Roses to benefit the Lance Armstrong Foundation. He established the foundation to benefit cancer research after being diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1996. After treatment, he was declared cancer-free in February 1997.

Armstrong rides for charity in May 1998 at the Ikon Ride for the Roses to benefit the Lance Armstrong Foundation. He established the foundation to benefit cancer research after being diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1996. After treatment, he was declared cancer-free in February 1997.  Armstrong takes his honor lap on the Champs-Élysées in Paris after winning the Tour de France for the first time in 1999.

Armstrong takes his honor lap on the Champs-Élysées in Paris after winning the Tour de France for the first time in 1999.  After winning the 2000 Tour de France, Armstrong holds his son Luke on his shoulders.

After winning the 2000 Tour de France, Armstrong holds his son Luke on his shoulders.  Armstrong rides during the 18th stage of the 2001 Tour de France. He won the tour that year for the third consecutive time.

Armstrong rides during the 18th stage of the 2001 Tour de France. He won the tour that year for the third consecutive time.  Armstrong celebrates winning the 10th stage of the Tour de France in 2001.

Armstrong celebrates winning the 10th stage of the Tour de France in 2001.  After winning the 2001 Tour de France, Armstrong presents President George W. Bush with a U.S. Postal Service yellow jersey and a replica of the bike he used to win the race.

After winning the 2001 Tour de France, Armstrong presents President George W. Bush with a U.S. Postal Service yellow jersey and a replica of the bike he used to win the race.  Armstrong celebrates on the podium after winning the Tour de France by 61 seconds in 2003. It was his fifth consecutive win.

Armstrong celebrates on the podium after winning the Tour de France by 61 seconds in 2003. It was his fifth consecutive win.  Jay Leno interviews Armstrong on "The Tonight Show" in 2003.

Jay Leno interviews Armstrong on "The Tonight Show" in 2003.  After his six consecutive Tour de France win in 2004, Armstrong attends a celebration in his honor in front of the Texas State Capitol in Austin.

After his six consecutive Tour de France win in 2004, Armstrong attends a celebration in his honor in front of the Texas State Capitol in Austin.  Armstrong arrives at the 2005 American Music Awards in Los Angeles with his then-fiancee Sheryl Crow. The couple never made it down the aisle, splitting up the following year.

Armstrong arrives at the 2005 American Music Awards in Los Angeles with his then-fiancee Sheryl Crow. The couple never made it down the aisle, splitting up the following year.  Armstrong holds up a paper displaying the number seven at the start of the Tour de France in 2005. He went on to win his seventh consecutive victory.

Armstrong holds up a paper displaying the number seven at the start of the Tour de France in 2005. He went on to win his seventh consecutive victory.  As a cancer survivor, Armstrong testifies during a Senate hearing in 2008 on Capitol Hill. The hearing focused on finding a cure for cancer in the 21st century.

As a cancer survivor, Armstrong testifies during a Senate hearing in 2008 on Capitol Hill. The hearing focused on finding a cure for cancer in the 21st century.  In 2009, Armstrong suffers a broken collarbone after falling during a race in Spain along with more than a dozen other riders.

In 2009, Armstrong suffers a broken collarbone after falling during a race in Spain along with more than a dozen other riders.  Young Armstrong fans write messages on the ground using yellow chalk ahead of the 2009 Tour de France. He came in third place that year.

Young Armstrong fans write messages on the ground using yellow chalk ahead of the 2009 Tour de France. He came in third place that year.  Armstrong launches the three-day Livestrong Global Cancer Summit in 2009 in Dublin, Ireland. The event was organized by his foundation.

Armstrong launches the three-day Livestrong Global Cancer Summit in 2009 in Dublin, Ireland. The event was organized by his foundation.  In May 2010, Armstrong crashes during the Amgen Tour of California and is taken to the hospital. That same day, he denied allegations of doping made by former teammate Floyd Landis.

In May 2010, Armstrong crashes during the Amgen Tour of California and is taken to the hospital. That same day, he denied allegations of doping made by former teammate Floyd Landis.  Ahead of what he said would be his last Tour de France, Armstrong gears up for the start of the race in 2010.

Ahead of what he said would be his last Tour de France, Armstrong gears up for the start of the race in 2010.  Lance Armstrong looks back as he rides in a breakaway during the 2010 Tour de France.

Lance Armstrong looks back as he rides in a breakaway during the 2010 Tour de France.  Armstrong finishes 23rd in the 2010 Tour de France. He announced his retirement from the world of professional cycling in February 2011. He said he wants to devote more time to his family and the fight against cancer.

Armstrong finishes 23rd in the 2010 Tour de France. He announced his retirement from the world of professional cycling in February 2011. He said he wants to devote more time to his family and the fight against cancer.  Armstrong's son Luke; twin daughters, Isabelle and Grace; and 1-year-old son, Max, stand outside the Radioshack team bus on a rest day during the 2010 Tour de France.

Armstrong's son Luke; twin daughters, Isabelle and Grace; and 1-year-old son, Max, stand outside the Radioshack team bus on a rest day during the 2010 Tour de France.  The frame of Armstrong's bike is engraved with the names of his four children at the time and the Spanish word for five, "cinco." His fifth child, Olivia, was born in October 2010.

The frame of Armstrong's bike is engraved with the names of his four children at the time and the Spanish word for five, "cinco." His fifth child, Olivia, was born in October 2010.  In February 2012, Armstrong competes in the 70.3 Ironman Triathlon in Panama City. He went on to claim two Half Ironman triathlon titles by June. He got back into the sport after retiring from professional cycling.

In February 2012, Armstrong competes in the 70.3 Ironman Triathlon in Panama City. He went on to claim two Half Ironman triathlon titles by June. He got back into the sport after retiring from professional cycling.