- Penn State students rally to redefine their school after being plagued by scandal

- "Now it's not just football, it's about the school," senior Tyler Franks says

- Students say they will always remember victims and also have pride in school

- Some students say they won't be proud to support football

State College, Pennsylvania (CNN) -- A roar echoes through the arena. From the packed stands a chant begins: "We Are." Voices boom louder in response: "Penn State." For nearly 10 minutes, the chants reverberate.

This is not a football game, or any sports event. It is the freshman convocation, the official welcome for the incoming class. More than 7,000 new students are in the Bryce Jordan Center making themselves heard.

They are here.

They are here despite a scandal that has damaged this school's reputation, brought unprecedented sanctions from the National Collegiate Athletic Association, jailed a former football coach for sex abuse and prompted an ongoing investigation into allegations of a coverup by top officials.

Emotional return to gridiron for Penn St

Emotional return to gridiron for Penn St  New PSU coach: You run & hide or attack

New PSU coach: You run & hide or attack  PSU player: I'm not leaving this team

PSU player: I'm not leaving this team  Bowden: 'Not rejoicing' over win record

Bowden: 'Not rejoicing' over win record But they are here. They are proud. Some are also angry.

As their chants grow louder and they wait to hear new President Rodney Erickson welcome them, some stand. They are decked out in blue and white, with shirts that say "I still bleed Blue and White" or "Penn State Proud."

Others strike a different chord. "WE ARE... PISSED OFF" one shirt says. Another has NCAA written on the front -- the C replaced with the Bolshevik hammer and sickle. Underneath it says: "National Communist Athletic Association." "Overstepping Their Bounds And Punishing The Innocent Since 1906" is printed on the back.

These freshman did not live through the last year of turmoil at Penn State. But they face the same question so many others on this campus are struggling to answer: What does it mean now to say "We Are Penn State"?

For many, the phrase will unite them like never before and allow them to speak for themselves instead of listening to others define them. For some, the phrase has become a badge of shame.

It is still their rally cry, one that will be tested and scrutinized all year, but perhaps never more than on Saturday when the Penn State football team starts its season for the first time since 1966 without Hall of Fame coach Joe Paterno.

Penn State alum: 'We are more than this tragedy'

The chants that ring out in the Bryce Jordan Center are echoed along the main streets of campus during the first week of school. They are the culmination of nine months of unrelenting anger and frustration. It is the first time the students have come together since former assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky was found guilty of sexually abusing 10 boys over a period of 15 years.

As the convocation begins, a group of freshman girls whisper among themselves, wondering if his name will come up.

It doesn't. Well, not outright.

"You are part of one of the best universities in America, an institution that is known nationally and internationally for excellence in teaching, research and service," Erickson says. "Unfortunately, over the last nine months, Penn State has also become known for a number of other issues that have, in many cases, overshadowed the many outstanding activities at Penn State. I assure you we are addressing those challenges and I promise you that we will emerge as a stronger, better university."

Penn State alum: We deserved NCAA penalty

That task will be challenging. Two former university officials still face charges for allegedly lying to the grand jury that investigated Sandusky. Paterno was fired by the Board of Trustees for failing to take his knowledge of the scandal to appropriate authorities. He died two months later. After the lurid details of sexual abuse that emerged at trial, and a scathing report on how the university handled it, few kind words about the school are uttered outside of State College.

That, in part, is why the incoming class is so important, says student body president Courtney Lennartz. She speaks plainly to the freshmen:

"You stuck with Penn State when times were tough. That's something that takes a special kind of person. During a time when so many others turned their back on this university, you still believed in us. You believe in our core values -- honor, integrity, philanthropy and knowledge -- which, despite what some may say, are forever unwavering. And for that, I am eternally grateful."

Penn State to give back trophies

The energy is palpable; the students are fired up. Samantha Gavrity, from Staten Island, New York, says the spirit she feels inside the arena is part of the reason she chose Penn State.

The astronomy and astrophysics major says she never considered switching schools. She knows she will get a top-notch education here.

"The students here are more passionate about everything now," she says. "If anything, that's a good quality in a student body, that they still really care. It shows how much they love the school."

It will be up to her and her many classmates to carry the torch as the school reshapes its identity.

"Now that you're here, it's really up to all of us," Lennartz tells the freshmen. "We are responsible for continuing the incredible legacy that so many have paved before us. It's a unique moment in our university's history, and as a result, there's never been a more important class than yours."

'We are joined at the hip'

Across campus, near the famed Nittany Lion statue, thousands pack the university's Recreation Hall. It is the night before classes begin, and freshmen line the stands of the gymnasium that is home to one of the top volleyball teams in the country.

Most athletic facilities off-limits to public at PSU games

It's the last event of Welcome Week. They are here to learn the fight song of the 157-year-old university -- words they will be asked to shout from the bleachers of Beaver Stadium.

The school's Blue Band cues up the songs. The cheerleaders and dance squads pump up the crowd. And then the freshmen are introduced to someone who knows more, perhaps, than anyone about the odds these students face: the new football coach.

"This is a special night for me," says Bill O'Brien. "Because if you think about it -- myself and you, we're joined at the hip. Because we both committed to come to Penn State during what many people say are tough times.

"I don't see tough times," he says, looking out at the crowd decked out in blue and white. "I see this."

The stands shake and rattle.

It is apparent that the season-opening football game on Saturday signifies Penn State's chance to prove the world wrong, that there is more to this school than the scandal with which it has become synonymous.

But tucked away on a corner bleacher is one young woman who is not standing. Her head is down, buried in her purse. During a short lull, she darts for the exit.

"I can't take it. I can't fake it," she says outside in the hallway. "I know everyone is so excited, but I just can't pretend I'm proud right now."

Ali, an 18-year-old, whispers quietly outside that she isn't sure how much more she should say. She's afraid of what could happen if she gives her full name because she has no other school to go to and doesn't want any trouble.

"I didn't get accepted anywhere else," she says. "I have no choice but to come here. And I just can't sit in that room. After what I've heard all summer, after all the questions from friends and family. I thought I could do it, but I can't. What happened here is so awful and if in any way the administration looked the other way, that goes completely against the things I want in a school."

She hurries off just as O'Brien gives his parting words.

"We expect a home-field advantage like no other," he says. "We expect for Ohio University to come in here and not know what hit 'em."

The crowd erupts.

"So, let's stay committed, let's be loud and proud, and let's get this thing going," he says as the marching band strikes up.

As the freshmen exit, the chants continue. They walk back toward their dorms, but the shouts can be heard in the distance: "We Are."

Just outside the building, the last remaining students respond: "Still Penn State."

Pride in school rankings, not football scores

The day before classes start, Tyler Franks and Kaya Weaver sit on the edge of where campus ends and downtown begins. Nearly every storefront boasts a sign that says "Proud to support Penn State football."

Weaver and Franks, who are both seniors, epitomize that sentiment. They are Penn State "blue and blue," as they say here. They represent the third generation in their families to come to State College.

Franks says he has been waiting nine months to finally talk about all that has happened: How his school has been branded, why he thinks Penn State will rally back stronger than ever, why there is so much more to Penn State than the scandal that has enveloped it.

Penn State player: I'm not leaving

"We're going to show the world this is what Penn State is, especially come football season," he says. "Even if we win four games this year, the stadium is going to be packed because of the loyalty we have to the school. Now it's not just football, it's about the school."

The bells of Old Main chime in the background. It's the weekend, and the fight song rings out. The administration building may be the best-known sight on campus besides the football stadium. It was here that riots took place after it was announced that Paterno had been fired.

But as Weaver and Franks quickly interject, it is also the place where 10,000 people gathered with candles in their hands for a vigil for Sandusky's victims. Both seniors recall that powerful moment. That is the snapshot they want people to remember, not the misguided actions of a group one night last winter.

Franks says the depictions of his fellow classmates as blindly worshipping football -- and surrendering their values to that culture -- are not true. He points to a campus dance marathon known as THON, a yearlong charity event that raises millions of dollars for pediatric cancer.

"Everyone talks about the culture here. There is a culture at Penn State, but it's not a bad culture. That's not why this stuff happened. The culture at Penn State is a community that is just unbelievable. What we do for THON, that's the culture at Penn State."

The THON effort, run by the fraternity and sorority IFC/Panhellenic Council, culminates in a weekend marathon with participants dancing for 46 hours straight. Despite the scandal, the group brought in a record yearly total of $10.6 million last year. In its 40 years on campus, says the group's public relations chairperson, Cat Powers, it has raised more than $89 million.

The organization is a clear source of pride here. It is mentioned at every event during Welcome Week and heralded by students and alums.

Still, football has long received top billing. So it's no surprise the impact of the scandal is felt on campus.

"I know a couple of people who transferred out of here because their internships were being impacted," says Kelly Mullen, a senior from Scranton, Pennsylvania. "Because of the role that football and Joe Paterno played in Penn State history, it's affecting basically everything Penn State stands for -- even though it shouldn't."

Other students agree that football is king. But they are quick to rattle off school rankings (No. 45 for best schools in the U.S and No. 13 for public schools by U.S. News and World Report). They talk about top-notch research programs and their work with Space-X to revolutionize space travel. They want people to know that Penn State is about more than jocks and winning titles.

You can tell they relish the chance to gush. They're tired of what everyone has said about who they are and what they stand for. And they are frustrated, they say, to have been branded in many ways without the chance to defend themselves.

"It's not only about the football team, it's about our school regaining the strength that we've seem to lost a little bit," says Weaver, one of the third-generation Penn Staters. "There comes a point when enough is enough. It's time for us to turn around and say, 'Well you've had all this time to say things about our school, now let us show you, not tell you, how great of a place we really are.'"

A scoop of controversy, and a new legacy

In the center of campus, on the first day of school, students congregate at the Berkey Creamery. It's one of the most popular spots on campus, and a post-football game tradition.

Thomas Palchak, who has managed the creamery for 26 years, is also a Penn State graduate. He met his wife in a lab behind the creamery and their son attended school here, following in their footsteps.

Twenty years ago, the creamery wanted to invent some new ice cream flavors. It tweaked a peaches-and-cream recipe and dubbed it "Peachy Paterno." A slew of other flavors made here were named after campus icons and staples. One of them -- "Sandusky Blitz" -- has been scrapped now.

But the Paterno flavor still packs the freezers at the creamery, despite complaints and angry phone calls at Palchak's home over the past months.

"The flavor was meant to be a recognition of off-the-field, academic contributions, which were well known in that time," Palchak says, and, he believes, should still be recognized.

In the wake of a scandal that left many questions swirling about the coach known affectionately as JoePa, his status has become somewhat murky. His statue outside the football stadium was taken down. His name was removed from Nike's child-care center, and his status as major college football's winningest coach is erased.

The debate over the ice cream is one thing. But for Palchak, the scandal and the implications being drawn aren't something to take lightly. He believes a lot of unwarranted hatred is being heaped upon the university day after day.

"This was an individual, retired from the university, and he committed these awful deeds and he was tried and convicted and is now in jail. In a normal justice situation, he's going to pay for his crime and it is done," Palchak says. "But in this situation, what you see now is the collective community being penalized for the sin of one single person."

Palchak knows there's no escaping what happened here -- they will live with it forever. He just wishes people would recognize that not everyone associated with the school is to blame.

"It's now part of the DNA of the university, just like ... the Kent States of the world," he says. "This is now a part of us. We just have to look at it, learn from it and move on. But it has to be said that this became a very, very unfair portrayal of the university instead of the one individual."

That frustration is shared widely here. Perhaps the only thing more upsetting is when outsiders say the school is ignoring the victims in the sex abuse case by cheering and defending Penn State.

"Of course I feel bad for the kids, the kids that are now adults that this happened to. I don't think there is one person who doesn't feel that way," says Tyler Franks, one of the third-generation seniors. "But that doesn't mean I'm not allowed to show pride and love in my school."

Come Saturday, students will likely come out in force to do just that. Things will be different, of course: from the players on the team, to their uniforms, to the expectations of what success will mean in the upcoming years. It will also be the first time in 46 years that Joe Paterno will not lead the team out of the tunnel and onto the field.

"It's going to be weird, but it's going to be cool that we're a part of two legacies," says Franks. "Joe Paterno, the end of his legacy, and the start of Bill's legacy here. It's sad and exciting."

It is, in many ways, the writing of a new chapter. It will define anew what it means when crowds outside and inside the football stadium shout at the top of their lungs, "We Are Penn State."

Kicking off a new era of football at Penn State, with a hope and a prayer

A mural on College Avenue in State College, Pennsylvania, features former Penn State football coach Joe Paterno. Artist Michael Pilato put a halo over Paterno after the coach's death. When an investigation found that Paterno helped cover up child sex abuse by a former assistant coach, the halo was painted over.

A mural on College Avenue in State College, Pennsylvania, features former Penn State football coach Joe Paterno. Artist Michael Pilato put a halo over Paterno after the coach's death. When an investigation found that Paterno helped cover up child sex abuse by a former assistant coach, the halo was painted over.  Beaver Stadium, with a seating capacity of more than 106,000, is home to the Penn State football team.

Beaver Stadium, with a seating capacity of more than 106,000, is home to the Penn State football team.  On the first day of classes, Penn State students talk on the phone and study outside the HUB, the student union center.

On the first day of classes, Penn State students talk on the phone and study outside the HUB, the student union center.  Wide receiver Evan Lewis, No. 37, gets ready for a drill with teammates during football practice on Tuesday, August 28. The Nittany Lions face Ohio at home under the direction of new head coach Bill O'Brien for the first game of the season on Saturday.

Wide receiver Evan Lewis, No. 37, gets ready for a drill with teammates during football practice on Tuesday, August 28. The Nittany Lions face Ohio at home under the direction of new head coach Bill O'Brien for the first game of the season on Saturday.  A videographer films the Penn State Nittany Lions during football practice.

A videographer films the Penn State Nittany Lions during football practice.  Students walk through campus on the first day of class on Monday, August 27. The campus is home to more than 40,000 students.

Students walk through campus on the first day of class on Monday, August 27. The campus is home to more than 40,000 students.  A car parked in a garage on campus has a license plate message directed at the former Penn State football coach.

A car parked in a garage on campus has a license plate message directed at the former Penn State football coach.  A man sits on College Avenue, the main drag that is lined by shops and restaurants.

A man sits on College Avenue, the main drag that is lined by shops and restaurants.  The jury chairs in the courtroom where Sandusky stood trial sit empty at the Centre County Courthouse in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania. Sandusky was found guilty of 45 counts of sexual abuse of young boys over a 15-year period. Sandusky has yet to be sentenced.

The jury chairs in the courtroom where Sandusky stood trial sit empty at the Centre County Courthouse in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania. Sandusky was found guilty of 45 counts of sexual abuse of young boys over a 15-year period. Sandusky has yet to be sentenced.  A student studies on campus.

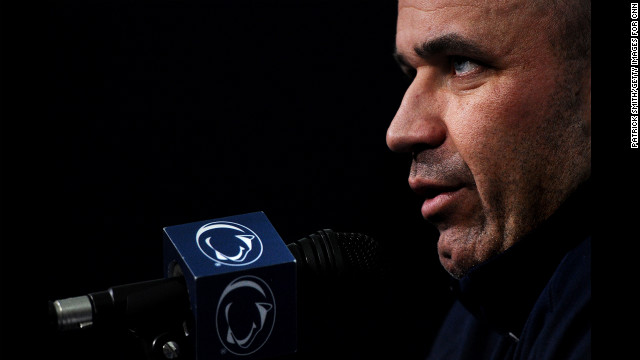

A student studies on campus.  Penn State head football coach Bill O'Brien speaks to the media during a press conference at Beaver Stadium on Tuesday, August 28. O'Brien will lead the Penn State football program for the first time on Saturday.

Penn State head football coach Bill O'Brien speaks to the media during a press conference at Beaver Stadium on Tuesday, August 28. O'Brien will lead the Penn State football program for the first time on Saturday.  "Peachy Paterno" ice cream sits in the freezer at the Berkey Creamery on campus. The "Sandusky Blitz" flavor has been removed.

"Peachy Paterno" ice cream sits in the freezer at the Berkey Creamery on campus. The "Sandusky Blitz" flavor has been removed.  The clock tower of the Old Main building peeks through the trees on campus.

The clock tower of the Old Main building peeks through the trees on campus.  The Blue Band, with a roster of more than 300 students, practices on the first day of school.

The Blue Band, with a roster of more than 300 students, practices on the first day of school.  Coach O'Brien speaks to the media. "No matter what happens on the field, these guys have developed an unbreakable bond."

Coach O'Brien speaks to the media. "No matter what happens on the field, these guys have developed an unbreakable bond."  A Paterno cutout stands inside a storefront window on College Avenue.

A Paterno cutout stands inside a storefront window on College Avenue.