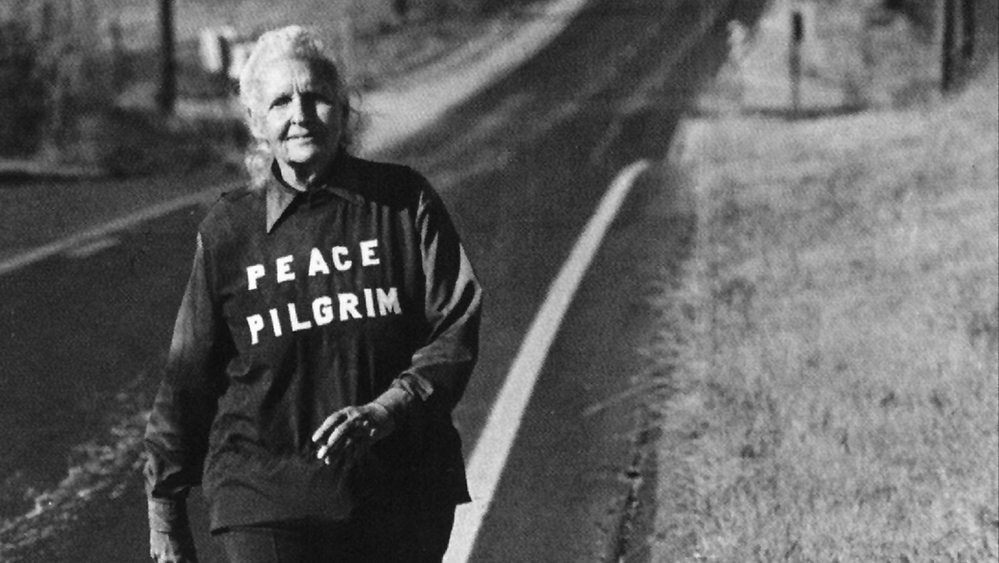

Peace Pilgrim had walked 25,000 miles by 1964, and continued for almost two more decades. She carried only a pen, a comb, a toothbrush and a map.

Peace Pilgrim had walked 25,000 miles by 1964, and continued for almost two more decades. She carried only a pen, a comb, a toothbrush and a map.

Courtesy of Friends Of Peace PilgrimIn 1953, Mildred Norman set off from the Rose Bowl parade on new year's day with a goal of walking the entire country for peace. She left her given name behind and took up a new identity: Peace Pilgrim.

When Peace Pilgrim started out, the Korean War was still underway and an ominous threat of a nuclear attack was on the mind of many Americans. And so, with "Peace Pilgrim" written across her chest, she began walking "coast to coast for peace."

For 28 years â€" the entire length of her journey â€" she never used money. She gave new meaning to the word minimalist, wearing the same clothes every day: blue pants and a blue tunic which held everything she owned â€" a pen, a comb, a toothbrush and a map. That's it.

"And I own only what I wear and carry. I just walk until given shelter, fast until given food," she says. "I don't even ask; it's given without asking. I tell you, people are good. There's a spark of good in everybody."

Mildred Norman at 16, when, as her sister says, "she had to have the latest clothing." When she devoted herself to walking for peace, she took on a completely different kind of life.

Mildred Norman at 16, when, as her sister says, "she had to have the latest clothing." When she devoted herself to walking for peace, she took on a completely different kind of life.

Courtesy of Friends Of Peace Pilgrim'Doing Something Different'

In July 1981, the day before she died, Peace Pilgrim was interviewed by Ted Hayes, the manager of a small radio station in Knox, Ind.

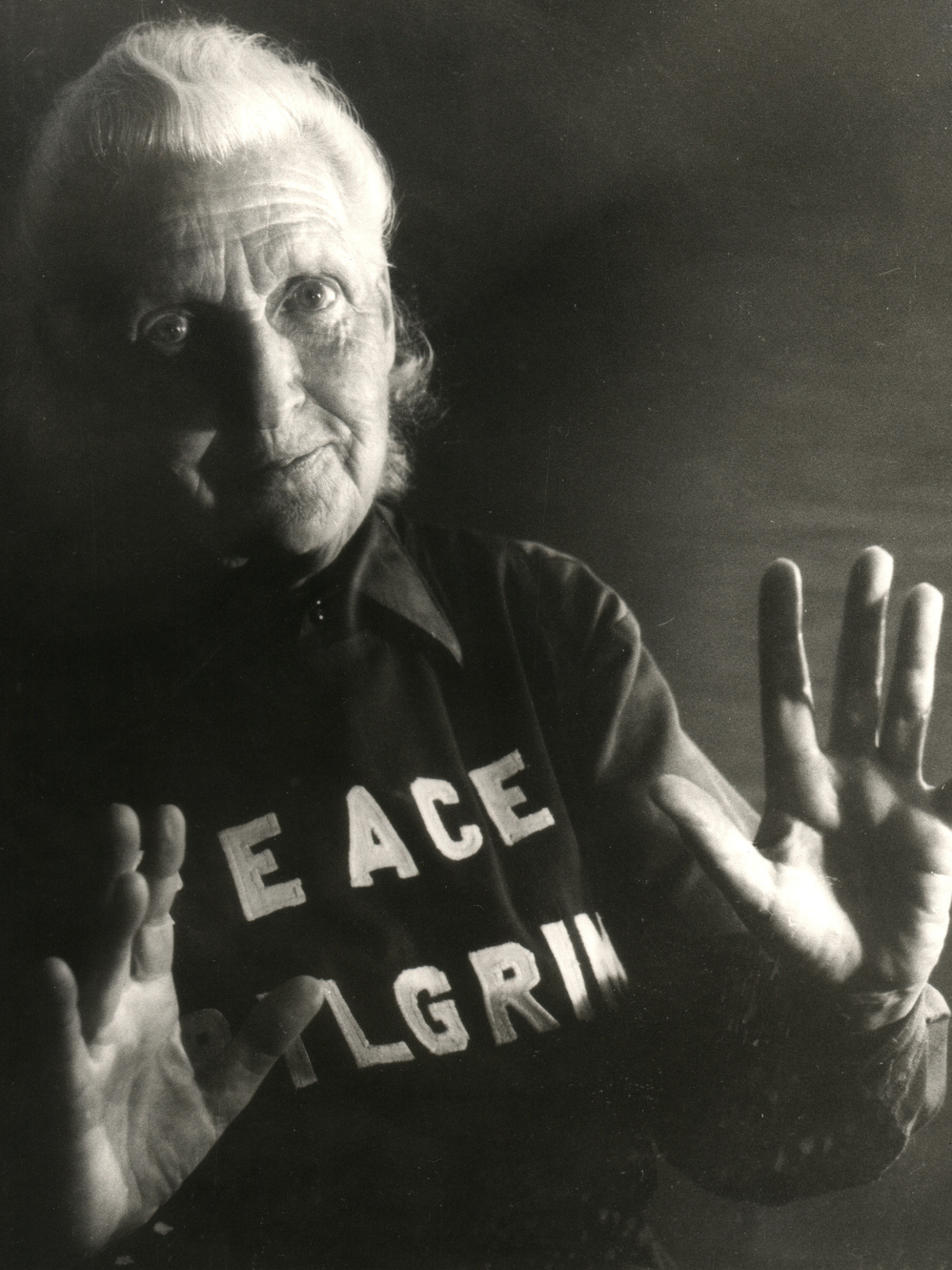

"Peace Pilgrim, you know there are a certain number of people who would probably think of somebody like yourself as a kook or a nut," Hayes said. "Do you have a problem overcoming this barrier with some people?"

"Well, I'm quite sure that some of those who have just heard of me must think I'm completely off the beam," Peace Pilgrim responded. "After all, I am doing something different. And pioneers have always been looked upon as being a bit strange.

"But you see, I love people and I see the good in them," she continued. "And you're apt to reach what you see. The world is like a mirror: if you smile at it, it smiles at you. I love to smile, and so in general, I definitely receive smiles in return."

One night, while driving on an Ohio road, book publisher and editor Richard Polese saw Peace Pilgrim, "kind of dashing a bit out of the way of the traffic on the road. And I had no idea who it was," he recalls. Years later, Polese met Peace Pilgrim and the two became friends.

Peace Pilgrim once described her childhood on a small farm on the outskirts of Egg Harbor, a small town two miles from Cologne, N.J., as a "very quiet life ... I had a woods to play in, and a creek to swim in and room to grow."

Peace Pilgrim's sister, Helene Young, 97, says Mildred Norman "was very much what they called a flapper in those days. She had to have the latest clothing. So, she made so many changes in her life to a very simple, basic life," Young says.

"We were brought up without a formal religion or politics," Young adds. "We were taught to think for ourselves, not follow the sheep."

A Walk In The Woods Becomes A Pilgrimage

"During the early years of my life, I discovered that money-making was easy but not satisfying," Young once explained. And one night in the late 1930s, "out of a feeling of deep seeking for a meaningful way of life," Peace Pilgrim began walking through the woods.

"And after I had walked almost all night, I came out into a clearing where the moonlight was shining down. And something just motivated me to speak and I found myself saying, 'If you can use me for anything, please use me. Here I am, take all of me, use me as you will, I withhold nothing,'" Peace Pilgrim recalled. "That night, I experienced the complete willingness, without any reservations whatsoever, to give my life to something beyond myself."

Peace Pilgrim acknowledged that some may have considered her kooky. But, she once said, "pioneers have always been looked upon as being a bit strange."

Peace Pilgrim acknowledged that some may have considered her kooky. But, she once said, "pioneers have always been looked upon as being a bit strange."

Courtesy of Friends Of Peace PilgrimFifteen years passed between this striking moment of clarity and the official beginning of her pilgrimage. To prepare, one of the things Peace Pilgrim did was walk the entire length of the Appalachian Trail in one year â€" the first woman to do so.

"She was not interested in being a mother, and that was why she knew that she could handle the pilgrimage, because she did not leave family behind," her sister Helene Young explains. "She and her husband were divorced, because she thought he should be a conscientious objector and his sergeant told him that was grounds for divorce."

The first year of her walk, Peace Pilgrim was thrown into jail for vagrancy, Young explains. "And they found out she wasn't a commie so they let her go."

But Richard Polese says his friend had no fear of jail. "She felt that jails were wonderful places to carry on the mission," he says. "She would gather the women prisoners together and teach them a little song, a little chant called 'the fountain of love.'"

The motto Peace Pilgrim had sewn on the back of her tunic when she started out, "walking coast to coast for peace," quickly became outdated. By 1964 she had already walked 25,000 miles. Eventually, she stopped counting.

A Fateful Speaking Engagement

As she became more well-known, Peace Pilgrim began getting invitations to speak at schools and churches. Which is what brought her to Knox, Ind., in the summer of 1981. That's where a woman who had spent her life walking through every state and most of Canada lost her life riding in a car.

Tony and Terry Bau, who run Bau Collision Repair, were outside in the yard when the accident occurred.

"I got on the side of her, she was still alive when I got up there," Terry recalls. "I was talking to her, just telling her everything would be OK."

"Even though we didn't know her â€" we didn't know any of her writings or anything like that â€" we still lived her life," Tony says. "'Cause I believe in exactly what she believes in: being free and try to have a more peaceful world amongst people."

Peace Pilgrim's journey ended on the side of that road in Indiana 30 years ago, but her followers say they continue to find meaning in her message and to be inspired by her example.

On the radio program the day before her death, host Ted Hayes read Peace Pilgrim's vow aloud: "'I shall remain a wanderer until mankind has learned the way of peace, walking until I am given shelter and fasting until I am given food.'

And, he added, "She appears to be a most happy woman."

"I certainly am a happy person," Peace Pilgrim responded. "Who could know God and not be joyous? I want to wish you all peace."