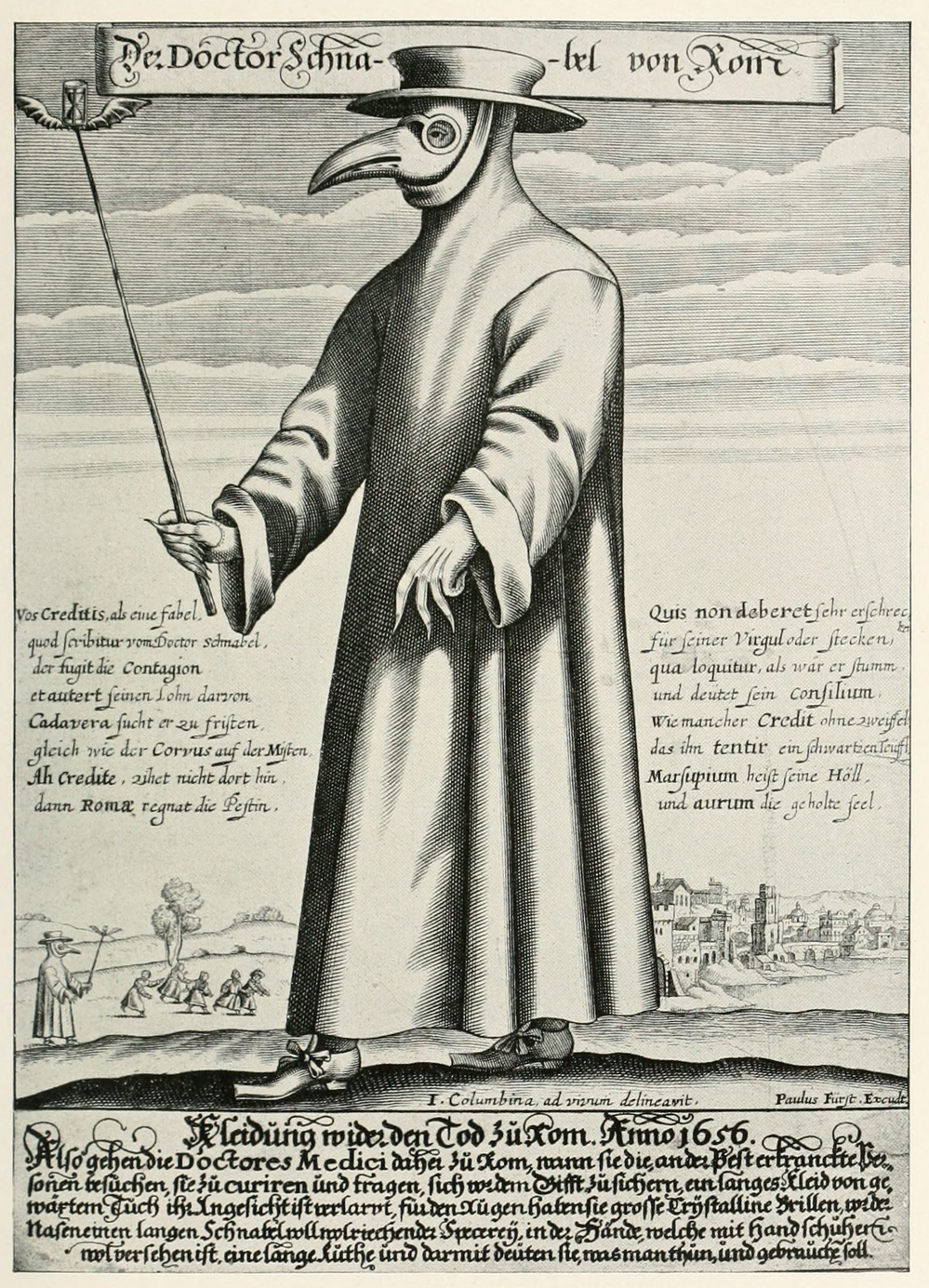

A copper engraving from 1656 shows a plague doctor in Rome wearing a protective suit and a mask.

A copper engraving from 1656 shows a plague doctor in Rome wearing a protective suit and a mask.

Artwork by Paul Furst /Wikimedia.orgThere's no doubt that the plague has staying power.

The deadly bacterium has probably been infecting people for 20,000 years. And, its genes have hardly changed since it killed nearly half of Europe's population during The Black Death.

Now microbiologists have evidence that strains of the plague may be able to reactivate themselves and trigger new outbreaks â€" even after lying dormant for decades.

That's the conclusion of a study just published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, which looked at recent plague outbreaks in Algeria and Libya.

In Algeria, as in many parts of the world, the plague was thought to be pretty much extinct. But plague cases cropped up there in 2003 and again in 2008.

Then in 2009, the disease appeared in neighboring Libya, after what had been a 25-year hiatus.

Some epidemiologists assumed that the plague bacteria had simply hopped across the Algerian border into Libya. Flea bites can infect a person, and the fleas love hanging out on rats and other mobile rodents.

But microbiologist Elisabeth Carniel wasn't so sure about the Algerian connection.

She thought that, perhaps, the bacterium could have somehow reactivated itself in Libya and started infecting people after a long dormancy.

So she and her team at the Institut Pasteur in Paris compared the DNA from the bacteria in Libya with samples from Algeria.

The two sets of sequences didn't match up. The plague in Libya most closely resembled bacteria that originated in Central Asia thousands of years ago, while the Algerian plague looked like a strain that probably came from Vietnam during World War II.

"We think the plague is extinct in these places, but it's not," Carniel tells Shots. "The plague is still there."

Carniel says the plague is probably hiding out in rats and squirrels. "It's circulating in the rodent reservoirs," she says.

Her team didn't have access to bacteria from older outbreaks in Libya, so she couldn't say for sure that the new cases came directly from the old ones.

But, she says, there was other evidence â€" like fleas and rats infected with the same bacteria â€" supporting her conclusion that the plague can resurface in regions after years of silence.

This could spell trouble for countries that no longer are looking out for the bacteria, she says.

"In many places, like the former Soviet Union, surveillance for the plague has stopped because of financial reasons or because it was thought to be eliminated," she says. "I hope that I 'm wrong, but I'm afraid that the plague will reappear in this part of the world."

So what triggers its reemergence?

No one knows for sure, Carniel says. But the outbreak in Libya came right after an especially humid winter, and fleas love humidity, she says. Plus, farmers had a bumper crop that season, which probably increased the rat population.

Carniel thinks that weather changes and increased development around the world could shift where the plague shows up.

Indeed, the bacteria has already shown signs of reactivation elsewhere. India had large outbreak in 1994 after 30 years of being free of plague.