Microbiologist Emma Allen-Vercoe invented the Robogut, a mechanical device that mimics conditions in the human colon.

Microbiologist Emma Allen-Vercoe invented the Robogut, a mechanical device that mimics conditions in the human colon.

Courtesy of thestar.comLast summer, we learned about fake poop made from soy beans that The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation used to test high-tech commodes at their toilet fair.

Now, we've come across another type of artificial poop, and it's being created to help people with really bad cases of diarrhea.

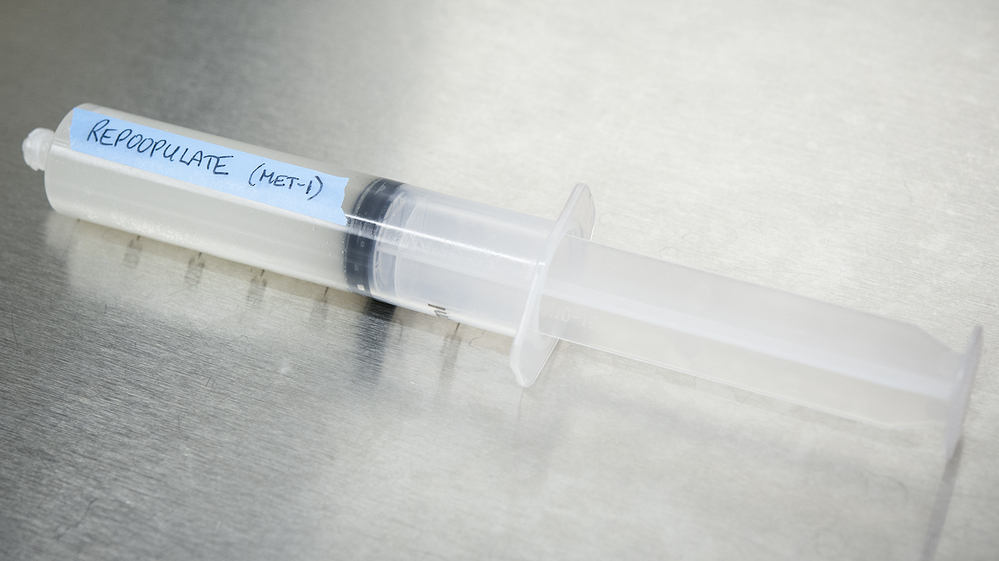

This synthetic stool isn't made of soybeans, but instead, it's a mixture containing 33 different types of bacteria. And, oh yeah, doctors create the stuff in something called the " Infectious disease specialists in Ontario, Canada, developed the synthetic stool â€" which they call RePOOPulate â€" to treat people sick with infections from Clostridium difficile, a bacterium that can cause serious, persistent bouts of diarrhea. The germ can take hold after people are treated with antibiotics for other infections. The Robogut, developed at the University of Guelph, can grow up a whole the bacteria that thrive in your gut. Many of these bugs won't grow in any other laboratory in the world. The researchers report in the current issue of Microbiome that the treatment with synthetic poop successfully cured two people of their infections. Normal bacteria in your gut help protect against toxic pathogens, Dr. Elaine Petrof, who led the study, tells Shots. "When you're sick and take antibiotics, you knock out the innocent bystanders, too." That messes up the ecosystem in your gut. Most people can repopulate the good bacteria naturally, but in some cases, C. difficile, which is resistant to many antibiotics, takes over. The bacteria make a nasty toxin that can make people get really sick. Taking more antibiotics usually wipes out C. difficile. But in some cases, Petrof says, the pathogen just keeps coming back. "It becomes a vicious cycle because the antibiotics keep killing the good bacteria." That's where the RePOOPulate could be helpful. The idea is to load up the patient's GI tract with a bunch of the good bacteria so they push C. difficile out of the way. To do that, Petrof and her team took a stool sample from a healthy, 40-year-old woman, who hadn't taken antibiotics in 10 years. Microbiologist Emma Allen-Vercoe, who invented the Robogut, grew the bacteria from her stool and then sequenced the bugs' DNA to figure which species were present. A stool substitute, called RePOOPulate, aims to replace dangerous pathogens in the gut with a healthy community of bacteria. A stool substitute, called RePOOPulate, aims to replace dangerous pathogens in the gut with a healthy community of bacteria. Using her clinical experience, Petrof selected 33 bacteria that she knew were healthy. The result was an opaque mixture of bacteria, which Allen-Vercoe describes as a "vanilla milkshake." Really. Petrof then put the bacterial cocktail into the intestines of the two patients during colonoscopies. The new bacteria slowly grew in the patients' guts and pushed out the toxic C. difficile. Both patients eventually stopped having diarrhea, and the transplanted bacteria were still present six months after the procedure. Petrof refers to the bacteria elixir as a probiotic, but she says it's far from the kind you pick up at Whole Foods. "Most probiotics are lab-extracted strains of bacteria, which are used in the dairy industry," she says. They aren't built to live in your gut, so they tend to just pass right through you after you take them, she says. In contrast, the bacteria in the RePOOPulate mixture have evolved to thrive in our gastrointestinal tracts. "That's where they normally live," she says. Plus, the mixture is a whole community of bacteria that live together in an ecosystem. "When you take antibiotics, it's kind of like stripping out the Amazon forest in your gut," she tells Shots. "We're putting the whole ecosystem back in." “ A fecal transplant is like taking a sledgehammer to kill C. difficile: It puts millions of bacteria into the patient. Gastroenterologist Darrell Pardi, who wasn't involved in the study, says the treatments is just one of several recent examples of doctors trying to develop a cleaner version of a fecal transplant. In that procedure, doctors take a stool sample from a healthy person and transplant it into the GI tract of a patient with C. difficile. Fecal transplants aren't approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and there are only a few reports out there showing how effective they are. "But they've gotten quite common in the past few years," says Pardi, who's studies experimental treatments for C. difficile at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. "More and more practitioners in the U.S. are doing fecal transplants, in both large and small centers," he tells Shots. "Our center has done 16 since September. Our success rate is similar to what's been reported, about 80 to 95 percent." But fecal transplants have a few problems, Pardi says. Each transplant requires a unique donor, so it's expensive. And, doctors really don't know which bacteria are getting moved between people. A pure culture of bacteria, like RePOOPulate, could be safer and more reproducible, Pardi says. "A fecal transplant is like taking a sledgehammer to kill C. difficile: It puts millions of bacteria into the patient," Pardi tells Shots. "There's tremendous enthusiasm now for finding what the key components of that hammer are."